The Impact of Rough & Tumble Play

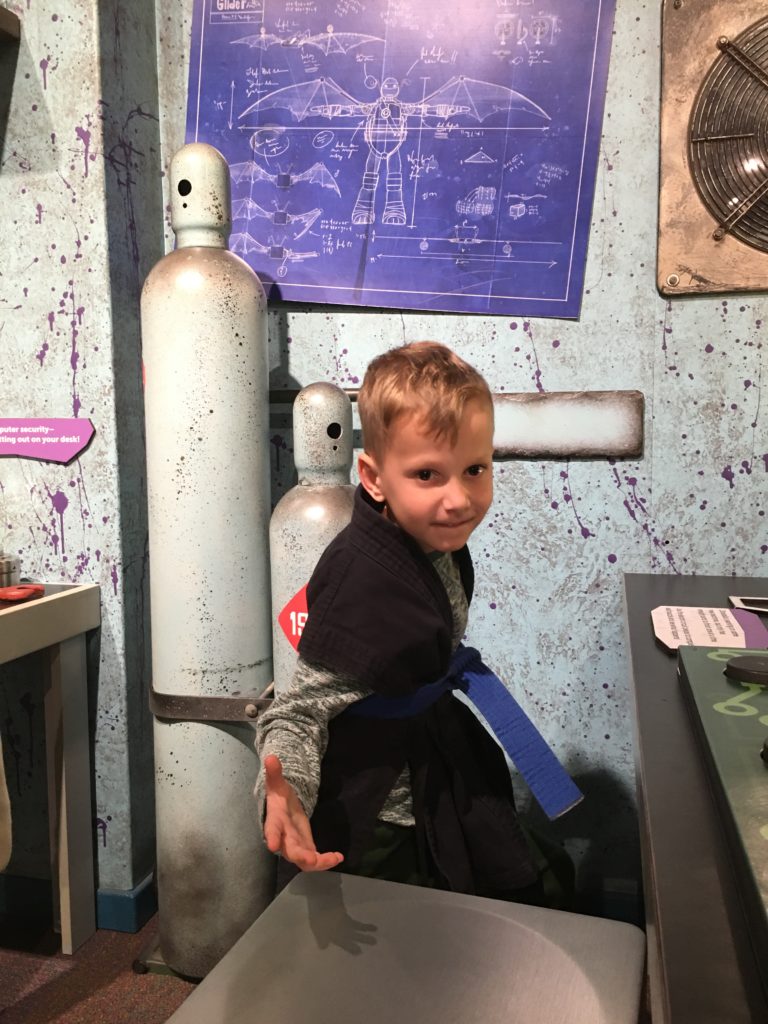

Rough and tumble play is all around us. Maybe you’ve noticed play wrestling, superhero battles replete with play punches and kicks or even a good old game of tag. Perhaps your little ones like to climb up and over their friends, tickle each other or spin themselves around. Each of these is an example of rough and tumble or “big body” play. While rough and tumble play can seem aggressive to on-lookers, and is consequentially often discouraged by grown-ups, this type of play is extremely widespread amongst youngsters (of most mammalian species!) and thought by scientists to provide kids with a number of benefits and opportunities to hone different skills.

Rough and tumble play is “playful contact or agonistic behavior that is performed in a playful mode and that is social in nature and characterized by positive emotion.”

Before we jump into the many benefits of rough and tumble play, first let’s clarify what rough and tumble play is and what it isn’t. Researchers have defined rough and tumble play as “playful contact or agonistic behavior that is performed in a playful mode and that is social in nature and characterized by positive emotion” (Colwell 2005). Rough and tumble play is characterized by several different behaviors including laughing, running, jumping, wrestling, chasing, fleeing and making play noise (Pellegrinni 1989). Children engage in rough and tumble play most around age seven when they spend an average of 13.3% of their free time playing this way. Preschoolers spend 5% of their play time engaged in rough and tumble play while nine-year olds spend 9.3% and 11-year olds use only 4.6% of their free time to rough and tumble play. Interestingly, this play type and dress-up are positively correlated, opening doors for rough and tumble play and interactive dramatic play to combine and create fantasy oriented rough and tumble play (Pellegrinni 1989). (Don’t you remember donning a hat or coat to battle dragons, pirates and wizards? I do!)

Rough and tumble play is not fighting, and while it certainly incorporates bodily contact it is not aggression. In rough and tumble play children use open-palmed hits, they smile and laugh, and they take turns playing the “aggressor” and “victim” roles. On the other hand, when children engage in genuine aggression, they are likely to use closed fists, mean faces and not laugh. However, research shows that in most cases rough and tumble play does not lead to aggression. In fact, one study found that only six in 67 instances of rough and tumble play resulted in genuine aggression (Brocker and Hartzog).

Grown-ups can help little ones have positive rough and tumble play experiences by setting ground rules and using different interventions to guide the play.

The following ground rules may be helpful:

- Contact is allowed below the shoulders only

- Use open palms – not fists

- Listen to others’ needs

- Everyone should be having fun

- Rough and tumble play is only okay outside on a soft surface (grass is great!) or where you have enough space.

A code word may be a helpful tool for children to use to let their friends know when the play needs to stop. Meanwhile, interventions like going over the rules before playtime and frequent check-ins can keep kids feeling good about the play. Check-in can simply be asking if everyone is having fun. With the right guidance from adults, kids can have a great time and reap the many benefits of rough and tumble play.

The benefits of rough and tumble play are social, physical and cognitive. There are several social benefits to rough and tumble play. During rough and tumble play children learn to send and receive social signals (in this case, the signs distinguishing playful vs. aggressive interactions). Since kids switch between “aggressor” and “victim” during play they also learn role alternation. This skill is necessary for other cooperative social interactions like holding a conversation. Because rough and tumble play is free from external goals it provides kids with the space they need to experiment with different social strategies. As a result, researchers hypothesize that rough and tumble play may foster kids’ ability to creatively solve social problems. All that from a pretend karate match or game of tag!

Rough and tumble play can be physically demanding and therefore linked to exercise of the cardiovascular system. (A game of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles vs. Shredder is excellent cardio!) The physical nature of rough and tumble play means it also increases muscle growth, balance and general physical capacity. These are abilities kids use later when they begin to participate in games with rules and organized sports.

Research suggests that physical activity positively impacts the brain and improves cognition, mood, attention and academic achievement in students. “Research shows even short bursts of movement deliver big benefits for brain health and academic performance, relative to sitting quietly,” says Dr. Laura Chaddock-Heyman, a scientist specializing in movement and the brain. The physical activity children undertake when they rough and tumble play may lead to better performance on tests, reduce symptoms of ADHS like moodiness and inattentiveness, and generally improve cognitive development and enhance concentration. In short big body play can have big impact for your little one’s social, physical and cognitive development!

Additional Resources

Brocker, B. & Hartzog, K. (2007). A Teacher’s Guide to Rough and Tumble Play. Retrieved on March 30, 2016, from http://farpoint.fcs.uga.edu/facs/docs/RoughandTumbleStudy.pdf

Hillman, Charles H., et al. “Run for Your Life! Childhood Physical Activity Effects on Brain and Cognition.” Kinesiology Review, vol. 6, no. 1, 2017, pp. 12–21., doi:10.1123/kr.2016-0034.

Jarvis, Pam. “‘Rough and Tumble’ Play: Lessons in Life.” Evolutionary Psychology, vol. 4, no. 1, 2006, p. 147470490600400., doi:10.1177/147470490600400128.

Lindsey, Eric W., and Malinda J. Colwell. “Pretend and Physical Play: Links to Preschoolers Affective Social Competence.” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, vol. 59, no. 3, 2013, p. 330., doi:10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.59.3.0330.

Pellegrini, A.d. “What Is a Category? The Case of Rough-and-Tumble Play.” Ethology and Sociobiology, vol. 10, no. 5, 1989, pp. 331–341., doi:10.1016/0162-3095(89)90023-x.